|

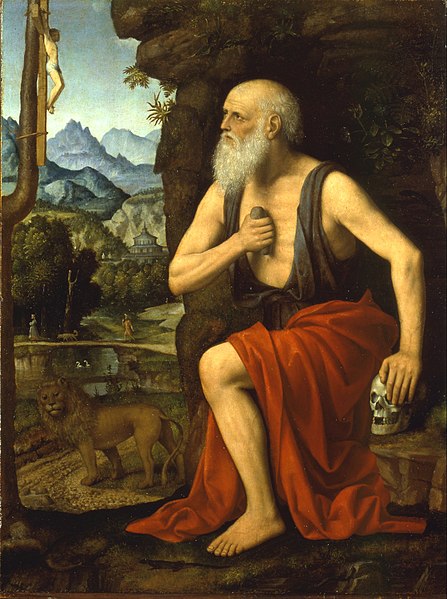

| 'Saint Jerome and the Lion,' (detail), Liberale da Verona, 15th century. |

Biographical

Overview

St. Jerome was born in c.347 in what was then part of

north-eastern Italy. As a student in Rome, he traversed the boundaries of wantonness

and piety. Later he spent time living in Gaul, during which he is believed to

have taken up his first theological studies.

At about the age of 26 he set out on a journey through

Thrace and Asia Minor, residing for the most part at Antioch. There, during an

illness, he had a vision that “led him to lay aside his secular studies and

devote himself to God. He seems to have abstained for a considerable time from

the study of the classics and to have plunged deeply into that of the Bible”.[1]

However, he never forsook the seeds of truth, goodness and beauty he had

gleaned from the ancient classics. Since throughout his letters, even in his

old age, he continued to quote from them – above all from Virgil.[2]

|

| Jan Hovaert, 1665-1668. |

Following his conversion of heart, Jerome started to live

an ascetic life in the desert of Chalcis. In 378 or 379 he returned to Antioch,

and against his preference was ordained a priest by Bishop Paulinus. He then

went to Constantinople, studying for two years under St. Gregory Nazianzus,

followed by three years in Rome as Pope St. Damascus’ protégé and secretary.

While in Rome Jerome was surrounded by a circle of

notable and well-educated Roman women who through his influence, longed for the

monastic life. The most well-known of these, are Saints Lea, Marcella and

Paula. Due to such acquaintances, in addition to a false allegation concerning

improper relations with the widow named Paula, and his unsparing criticism of

the worldliness of the clergy in Rome, he was soon compelled to leave Rome.

From Rome he went to Antioch, and then to Bethlehem.

There he ended up as the head of a small monastery, with an adjacent convent

where a group of women lived under St. Paula. Bethlehem remained Jerome’s home

for the next thirty-four years of his life and here he wrote the majority of

his works. Guiding numerous souls through his correspondences, and rebuffing

critics. With his letters enjoying a wide circulation in a crumbling Roman

Empire.

|

| 'Funeral of St. Jerome,' Filippo Lippi, 1452-1460. |

Yet it would be a mistake to think he lived all of these

final days in peace. For several years before his death, an angry mob raided

his monastic sanctuary, incumbent on exacting violence on Jerome for his

writings against the Pelagian heresy. In their wake they burnt the monastic

buildings and killed a deacon, but he himself was able to take refuge in a

nearby fortress, escaping unharmed. Four years later, in c.420 he died at the

age of 70.

Jerome’s Legacy

Since his death, Jerome has been recognised as an eminent

Church Father and as a Doctor of the Church. He is considered the patron of archeologists, archivists, biblical scholars, libraries, librarians, school children, students and translators. One can understand his patronages, since Jerome is responsible for translating

most of the texts of the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into Latin, in a

translation which was to be called the Vulgate. Even in his own day, he was

noted for his mastery of the scriptures, for his scriptural commentaries – on

various books of the Old and New Testaments; and for his numerous letters. St.

Augustine, who despite his at times rocky relationship of correspondence with

Jerome, referred to him in such titles as, “My Holy Brother” and “Fellow-Presbyter”, and stated

that “What Jerome is ignorant of, no mortal has ever known.”[3]

However, on the flip side of Jerome’s intellectual

prowess, linguistic eloquence, robust asceticism, spiritual mastery in matters

both abstract and practical, and his unwavering zeal for the faith, is the

portrait painted in regards to his personality: a stern, uncompromising man. Considered

at times to be excessive and exacting, who was a vehement satirist against his

doctrinal foes, and who had a boisterous temper.

Jerome’s

Tempestuous Side

Such negative depictions are not unfounded in the least,

for his correspondences prove he had a temper and a sharp pen. Although,

arguably, these ‘outbursts’ never seem to be totally unfounded or unprovoked. Nor

are they without their humour. A humour which it seems at times has been mistaken

by commentators for outright aggression.[4] Indeed,

as Andrew Cain points out, Jerome’s Letters are often read out of context. For

Jerome is writing in a time where letter-etiquette was perhaps even more sensitive

as swift replies to texts are today, and where reproach and a certain theatricality

were rhetorical devices utilised in ancient Greco-Roman correspondence, beyond

what is perceived today as outright ‘meanness’ and arrogant ‘show-man ship’.[5] Nevertheless,

in his letters there is ample evidence of his tempestuous side which is

impossible to deny.

In Letter 8 addressed to the sub-deacon Niceas Jerome almost

whinges about his failure to respond to his letters. He writes:

You, however, who have but just

left me, have not merely unknit our new-made friendship; you have torn it

asunder… Can it be that the East is so hateful to you that you dread the

thought of even your letters coming hither? Wake up, wake up, arouse yourself

from sleep, give to affection at least one sheet of paper.[6]

Elsewhere we see Jerome’s sharp pen at work again. In

c.396, he responds to Vigilantius who has accused him of the heresy of

Origenism:

Christian modesty holds me back

and I do not wish to lay open the retirement of my poor cell with biting words.

[Que the biting words:] Otherwise I should soon show up all your bravery and

your parade of triumph… for my own part as a Christian speaking to a Christian

I beseech you my brother not to pretend to know more than you do... the stench

of the bilge water has affected your head... If you wish to exercise your mind…

learn logic, have yourself instructed in the schools of the philosophers; and

when you have learned all these things you will perhaps begin to hold your

tongue… Accordingly I may seem to have been somewhat more acrid in this latter

part of my letter than I declared I would be at the outset. Yet… it is

extremely foolish in you again to commit a sin for which you must anew do

penance. [7]

Angry-Jerome: A

Popular Portrait

A rather ‘lovely’ synopsis of Jerome’s character is

provided in volume six of the Prolegomena to Hendrickson Publisher’s Nicene

and Post-Nicene Fathers, drawing from William Smith’s Dictionary of

Christian Biography:

He was vain and unable to bear

rivals, extremely sensitive as to the estimation in which he was held by his

contemporaries, and especially by the Bishops; passionate and resentful, but at

times becoming suddenly placable; scornful and violent in controversy; kind to

the weak and the poor; respectful in his dealings with women; entirely without

avarice; extraordinarily diligent in work… There was, however, something of monkish

cowardice in his asceticism…[8]

|

| 'St. Jerome in Penitence,' Bernardino Luini, ~1525. |

And perhaps it suffices to end there, for despite some

unvarnished truths, it would do well to spare ourselves from some of the additional

nonsense written thereafter (concerning anti-middle age polemic in reference to

Jerome’s medieval legacy). But from this slightly biased portrait, we can see

the sort of portrait that is painted of Jerome. A portrait – one shade the less

here, one shade the more there – which is by far the most common, and which has

been perpetuated throughout the centuries, even until today, helped along in

recent times by J. N. D Kelly’s biography on Jerome.[9]

However, it is his apparent humility grounded in

self-awareness, and in his instance, manifested in a monastic life of penance

and prayer, that has generally been presented as his saving grace – the seal of

which is his sound, rich and scripturally charged doctrine. A saving grace which

we might say can be symbolised by a stone. For, Pope Sixtus V (1585-90) having

stopped before a painting of the penitent Jerome striking his breast with a

stone, is said to have wryly remarked, “You do well to carry that

stone, for without it the Church would never have canonized you”.[10]

What’s So

Appealing About this Grumpy Old Man?

It is often refreshing to hear of the human imperfections

that plagued the saints – a reminder that sanctity isn’t synonymous with

middle-class respectability, and that God can work with the most unworkable

clay. As Paul says, “Moreover we have this treasure [of Christ and His glory]

in earthen vessels, to show that the surpassing power and ableness belongs to

God and not to us.” (2 Cor 4:7).[11] This

is among the reasons why the narrative of Jerome’s imperfections, above all the

trait of his temper, has been passed down to us until this day.

|

| 'Jerome,' Lucas Cranach the Elder, 16th Century. |

It’s also uncommon for glimpses of the raw humanity of

the saints to be had – especially if they lived so long ago. Indeed, the legacy

of the saints might be said to generally become more polished as the ages tick

by. For in the absence of written evidence, or the lack thereof, of their

unpolished side, in combination with a historical separation from the oral

traditions surrounding the lives and characters of such saints – first

furnished in their earliest devoted following, but which frequently wanes indefinitely,

or periodically in subsequent generations – it seems only reasonable that

accounts pertaining to their imperfections might easily be lost through the

sift of time. Especially when pious consciousness typically favours the grand

and glorious deeds of the saints.

However, because of the Letters of Jerome,

we have a rare and honest insight into a man who’s not shy to showcase his

views and personality – warts and all – in his various correspondences. Hence,

having abounding evidence of Jerome’s ‘unpolished side’, his fragility is

almost championed, at once frowned upon – to the extent that his sainthood has

been questioned – and found amusing, exaggerated and frequently

taken out of context.[12] Meanwhile

Jerome serves as a kind of archetype of the ordinary humanity of the saints –

and that the God of holiness can flourish in the midst of our imperfection. Not

so much in spite of it, but to some extent because of it.

|

| 'St. Jerome,' Jan van Hemessen, 1543. |

Not that imperfection in and of itself necessarily begets

God’s favour; but that faith and trust in God in the face of our imperfection,

in the context of our sincere struggle to live the spiritual life, causes our

imperfections to turn from things that work against us, to things that work in

our favour (Rom 8:28). Just as the wounds of a sick man almost endear the

doctor’s attention towards him, by which he wins not only medical assistance,

but personal contact. Or as the smelly nappy of an infant draws its mother to

lovingly tend to it – to clean and freshen it, and to end by caressing and

hugging it. Shows of affection which the smelly nappy incidentally caused!

Likewise, our imperfections – those minor but persistent

blemishes in our personality and habits, which no matter what, seem to cling to

us like skin to a skinny face – surrendered to God with repentance, and borne

in happy trust that God loves us and will deliver us; cease to work against our

sanctification and start to work for it. Even to the point of edifying our

neighbours, in some mysterious and roundabout way! After all, Jerome’s temper is

edifying us over fifteen hundred years later in regards to the goodness and

mercy of God!

Sure, some might use Jerome to justify bad habits, and

others might miss the point completely by snarling at him as ‘a saint who just

got through the door’. But this isn’t what pointing out his temper is supposed

to do. It supposed to encourage us, and console us, that whilst we remain as

imperfect as we are despite our efforts and our surrendering to God – who alone

can make us holy – there is still hope for us. Not the wishful and watered down

hope thrown around by the world, which is simply doubt disguised as

positive-thinking – but the kind of hope that is sure and certain in the Person

of Christ. A hope which is the means of possessing what is believed. The very

kind of hope the Holy Spirit awakens in us, whenever we read the words of Paul

in faith: “When I am weak, I am strong.” (2 Cor 12:10); and before this, in the

same chapter, where Paul relates the words God said to him in the midst of

struggling with his ineptness to actualise his ideal of sanctity: “My power is

made manifest in weakness.” (2 Cor 12:8).

God’s

Tenderness and Jerome’s Temper

It's ironic that I started writing this article with the

intention of revealing the tender side to Jerome, and here I’ve written around

two thousand words, the majority of which revolve around his temper, without really

denying it, and without mentioning the word tender or its variants once within the body of the text.

Indeed, God’s Providence never fails. For although it

would seem that in order to make a case for Jerome’s tenderness would lie in setting

up arguments against Jerome’s temper, or at least by arguing he was less

tempestuous than is claimed – which on one level was partially my initial

intention – through the eyes of faith I cannot help but notice God is reminding

me as I write that “My power is made manifest in weakness”. Ergo, that God’s

tenderness, is made manifest in Jerome’s temper.

|

| 'St. Jerome in Penitence,' Titian, 1575. |

Sure, as our Lord said, “God alone is good” (Mk 10:18) and

therefore, anything within us which is good, is ultimately attributable to God,

whilst anything bad, to our fallen will. Thus God’s tenderness – on loan to

Jerome, as Jerome’s tenderness – which is clearly discernible in his writings,

and is testified by his saintly status, clearly coexisted with his temper which

as far as we’re aware, remained with him until the grave. Serving him during his

lifetime, in similitude to St. Paul, as a kind of humbling thorn in his side,

perhaps permitted by God to endure for his sake “of not becoming too exalted by

the abundance of” his knowledge and the severity of his asceticism (2 Cor 12:7).

Yet the coexistence of God’s tenderness and Jerome’s own

temper, within the same single man, wasn’t in spite of his temper, it was

somewhat because of it. As we have said, God’s tenderness dwelt and was made

manifest in Jerome’s temper. For Jerome’s temper being like a thorn in his side,

would have, after it’s fuse was lit, brought about sorrow, contrition and

self-knowledge, and therefore humility and the fruit of its authenticity:

greater trust in God. We know this, because this is how a saint becomes a

saint. Not that they become perfect in the infallible sense; but that they know

how to carry their false-self with all its failings to the peak of Calvary, in

the confident joy of salvation in Christ their Groom – never flagging in zeal

for the truth, and never abandoning prayer, nor the hope of beatitude. Even

when everything inside and outside of them, in the midst of their sincere but

imperfect efforts, is screaming at them “It’s hopeless.”

Jerome’s

Temper: From A Source of Curse to A Source of Blessing

As we read in the Scriptures “A just man sins seven times

a day.” (Prov 24:16). Yet in keeping with Teresa of Avila’s understanding: with

the saints, having being sanctified to a considerable extent during their life,

their figurative seven sins, we might generalise to say, are either

imperfections, distinct from sin, or involuntary venial sins. The wounds of

imperfection or venial sin (almost certainly involuntary at least in his latter

years), caused by his moments of immoderate or unnecessary anger, would,

following his sorrow, acts of humility etc., thus have turned from wounds

causing harm to his soul, or at least as obstacles to greater sanctity, into vessels

in which God’s Power could dwell. In this instance, as such a wound would have

been caused by his temper, by means of the reversing principle of

sanctification, it would have become a vessel for God’s Tenderness.

This process would not have been wrought abstractly, but

through a spiritual union with the wounds of Christ – whose wounds were, are,

and ever will be, vessels of every grace and heavenly virtue. Such is the

seeming paradox of Christianity – wounds caused by violence and sin, in Christ

and by the Holy Spirit, become vessels of peace wherein abides the balm of redemption.

|

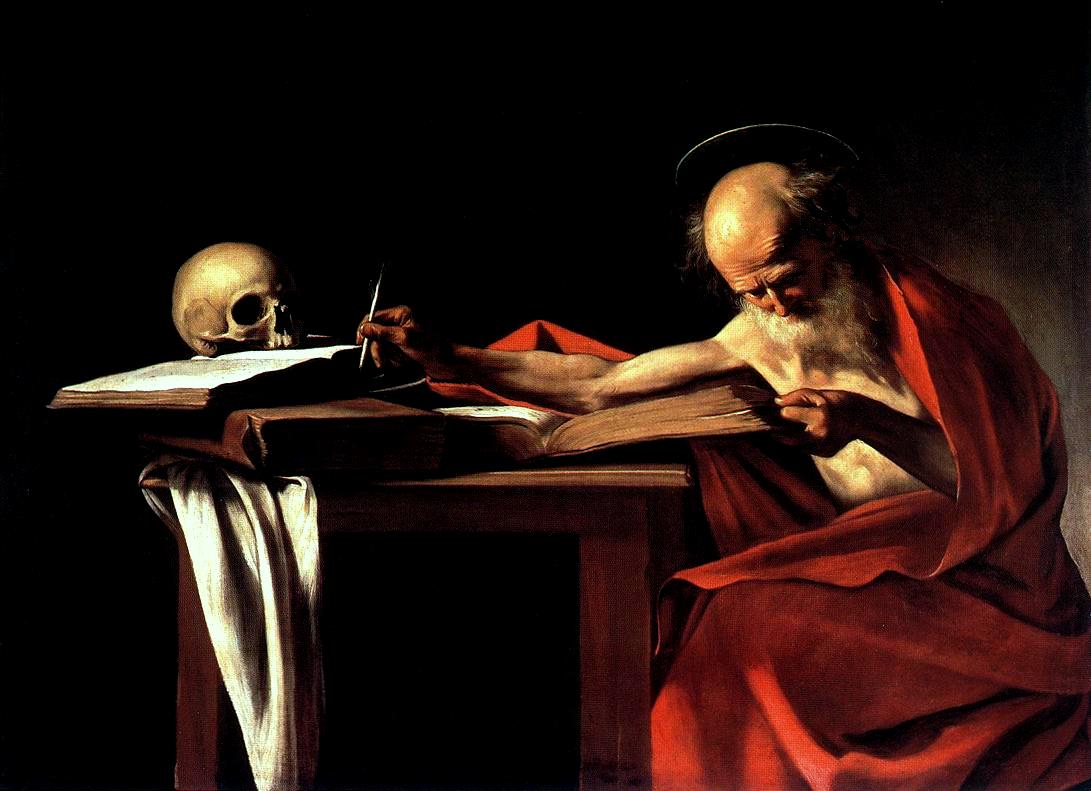

| 'Saint Jerome in His Study,' Caravaggio, 1605-1606 |

Hence Jerome’s temper, when it formed little wounds on

his soul, like pot holes on a road, became – through grace – the secondary means

by which he came to bear God’s tenderness within. With such grace likened to

rain when it fills pot holes and turns them into puddles. Puddles that reflect

the sun above when it glistens on their surface. Just as Jerome’s wounds caused

by anger, became through contrition and faith, like puddles for the Divine

tenderness, reflecting the light of God’s glory back unto Himself.

And indeed, even when a pothole becomes a puddle, the

pothole remains, just as Jerome’s temper – a natural inclination to anger

distinct from the act of anger itself – and weak moments of ‘losing it’, remained

throughout his life. Yet nevertheless, like Paul, St. Jerome could rejoice in

his weakness, because He knew that God’s tenderness was made manifest in his

temper. For who could attribute any shows of warmth and compassion, and tender

words, to a man known for his temper (and a hot temper at that!)? Especially if

such tenderness was nothing short of divine. Thus Jerome was an “earthen

vessel” to show the surpassing tenderness of God, for clearly it wasn’t his

own! (2 Cor 4:7).

Signs of Tenderness

in Jerome’s Letters

Before we conclude it seems only fair to provide some of

the written evidence of such tenderness – a tenderness he is not afraid to show.

Evidence which abounds in his extant Letters. We see Jerome’s tenderness

especially in his letters written in the consolatoria tradition. Particularly

in the letters of consolation, in the form of memoir, following the deaths of

the holy women whom he instructed in Rome. Some of whom followed him to

Bethlehem.

In Letter 127 addressed to Principia concerning St.

Marcella who died when the Visigoths sacked Rome in c.410. He writes:

I am so anxious myself to do

justice to her merits that it grieves me that you should spur me on and fancy

that your entreaties are needed when I do not yield even to you in love for

her.

|

| 'The sack of Rome by the Barbarians 410,' Joseph-Noël Sylvestre, 1890. |

He then goes on to state that his failure to expound on

Marcella’s life, for over two years, was not out of “a

wish to ignore her” as Principia had supposed, but to an incredible sorrow

which so overcame my mind that I judged it better to remain silent for a while

than to praise her virtues in inadequate language.” Before he ends the letter

we read of the tender way he handles the death of Marcella, whom died in

Principia’s arms – her best friend mind you – not simply as a rhetorician, but

as a friend, and above all, as a compassionate pastor who loves and cares for

his spiritual children as nothing short of a father:

When she closed her eyes, it was

in your arms; when she breathed her last breath, your lips received it; you

shed tears but she smiled conscious of having led a good life and hoping for

her reward hereafter. In one short night I have dictated this letter in honour

of you, revered Marcella, and of you, my daughter Principia[13]

Elsewhere we see the divine tenderness at work. In Letter

66 Jerome writes to a Pammachius concerning the loss of his young wife: “For

who can ears so dull or hearts so flinty as to hear the name of your Paulina

without weeping?”.[14]

Furthermore, in his longest letter, addressed to console the

son of St. Paula and expounding on her life following her death, he writes:

I have spent the labour of two

nights in dictating for you this treatise; and in doing so I have felt a grief

as deep as your own. I say in 'dictating' for I have not been able to write it

myself. As often as I have taken up my pen and have tried to fulfil my promise;

my fingers have stiffened, my hand has fallen, and my power over it has

vanished. The rudeness of the diction, devoid as it is of all elegance or

charm, bears witness to the feeling of the writer. And now, Paula, farewell… In

this letter

I have builtto your memory

a monument more lasting than bronze,which no lapse of time will be able to destroy.[15]

And finally, perhaps my favourite portion of text that I

have come across in Jerome’s Letters, is in a letter addressed to

Gaudentius (and in some sense to Gaudentius’ newborn daughter) who had asked

advice on how to raise his infant daughter. In this letter we see the tender

side to Jerome – the heart of a man who has clearly been touched by the Infant

Christ through his meditations on the Gospels. Yet by no means is such

tenderness polished and carefully courteous, as the beginning of the extract will

show, which is quite amusing:

It is hard to write to a little

girl who cannot understand what you say… For how can you speak of self-control

to a child who is eager for cakes, who babbles on her mother's knee, and to

whom honey is sweeter than any words? Will she hear the deep things of the

apostle when all her delight is in nursery tales? Will she heed the dark

sayings of the prophets when her nurse can frighten her by a frowning face?

He then reveals his acute grandfather-like-care:

…To induce her to repeat her

lessons with her little shrill voice, hold out to her as rewards cakes and mead

and sweetmeats. She will make haste to perform her task if she hopes afterwards

to get some bright bunch of flowers, some glittering bauble, some enchanting

doll… Then when she has finished her lessons she ought to have some recreation.

At such times she may hang round her mother's neck, or snatch kisses from her

relations. Reward her for singing psalms that she may love what she has to

learn. Her task will then become a pleasure to her and no compulsion will be

necessary.[16]

Conclusion

|

| 'Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome and Francis,' Paris Bordone, 1525. |

There is no denying that Jerome had a temper, and that he

often gave vent to it in less than ideal ways. Yet it is ludicrous to belittle

his sainthood on this basis. For one, we do not know the man personally, we

only have his letters which are written in a time different to our own, with its

own nuances of etiquette and humour. Two, his temper and his moments of

outburst enshrined in ink, may indeed often fall short of perfection, and there’s

no denying the frequent gruffness of his manner; but as far as we know, and the

Church seems to think it so, by the very fact of his canonisation, that he didn’t

wilfully inculcate his temper, or cling to his temper in pride, but rather it

was a thorn in his side! A wound that brought much suffering to his soul, and which

drove him into the desert of humility before his God. As such, the abiding

temper of Jerome, that he couldn’t seem to shake in spite of his penance and

prayers, testifies to his profound humanness. Which because he carried it with

such penitent humility, never wavering in his quest for God above, and in the

Presence of Jesus within the poor virgins and widows that relied on him as a

father, testifies to his profound saintliness. A raw and real saintliness which

in Jerome’s case looked like a grumpy old man around the edges and a tender

loving God in the middle.

In what is arguably Jerome’s last known letter, written to Augustine and Alypius - the date

of which we are certain, c.419 – we see his unpolished side, and the tenderness

of God at work. A tenderness expressed side by side with Jerome's usual gruffness. Although arguably in this instance it's more of a righteous than an unrighteous anger. He writes:

|

| 'St. Jerome,' Palma the Younger, 1595. |

This after all is the grumpy old man who can write: the

stench of the bilge water has affected your head, and the tender old man

who can write: she [your infant daughter] may hang round her mother's neck,

or snatch kisses from her relations.

Indeed, in Jerome we see that the Scripture is truly

alive: “The wolf shall dwell with the lamb” (Is 11:6). It

is tempting to change ‘wolf’ to ‘lion’ to fit the popular stated but non-existent

biblical phrase: “the lion shall dwell with the lamb,” because Jerome is often

depicted beside a lion, based on a legend that he tamed a lion by healing its

paw. Yet Jerome, the stickler for accurate biblical translation, would not

approve, and we wouldn’t want to stir the lion…the wolf… I mean… the lamb who

is tender (and who had a temper).

[1]

Wikipedia, “Jerome,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerome#Life

[2] I.e.

Among the many references, see Letters of St. Jerome: 66.5, 122.12 and 125.11.

[3] In

regards to titles of correspondence, see Letters of St. Augustine, 28, 82.

[4] Take

for example his letter to Julian a deacon of Antioch, which might be read as a

brazen reproach of his friend’s quick judgement as to why Jerome was failing to

correspond with him. Yet, really Jerome seems to be joking, since after

providing several excuses, he confesses the truth behind the matter of his delay

– illness.

[5] Andrew

Cain, “‘Vox Clamantis in Deserto’: Rhetoric, Reproach, and the Forging of

Ascetic Authority in Jerome’s Letters from the Syrian Desert,” The Journal

of Theological Studies 57, no. 2 (2006): 501, accessed 21 Oct 2016,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/23971716. Despite personally disagreeing with

aspects of his position, which argues Jerome is principally using his letters

as a means of personality propaganda, it is an excellent article.

[6] Jerome,

Letter 8 (VIII), in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.

[7]

Jerome, Letter 61.3 (LXI.3), in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.

[8] Prolegomena

to Jerome, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, vol.

6., trans. by W. H. Fremantle, G. Lewis and W. G. Martley, eds. Phillip Schaff

and Henry Wace (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers Marketing, 2012), xxxiii.

[9] “The

letters are approached in this way by Jerome’s four major twentieth century biographers:

G. Gru¨tzmacher, Hieronymus: Eine biographische Studie zur alten

Kirchengeschichte (Berlin, 1901–8), 3 vols.; F. Cavallera, Saint

Je´roˆme: Sa vie et son oeuvre (Paris, 1922), 2 vols.; J. N. D. Kelly, Jerome:

His Life, Writings, and Controversies (London, 1975); S. Rebenich, Hieronymus

und sein Kreis: Prosopographische und sozialgeschichtliche Untersuchungen

(Stuttgart, 1992).” Cain’s ninth footnote in “‘Vox Clamantis in Deserto’:

Rhetoric, Reproach, and the Forging of Ascetic Authority in Jerome’s Letters

from the Syrian Desert.”

[10] D.

Attwater and H. Thurston eds., Butler’s Lives of the Saints, vol. 3 (New

York: 1956), p. 691.

[11] δυνάμεως

is often translated simply as “power” but the word also means “ability” and so

the translation above incorporates this (even if some might argue ableness is

not a real word!).

[12]

In regards to his sainthood being questioned, see Andrew Cain, “‘Vox Clamantis

in Deserto’: Rhetoric, Reproach, and the Forging of Ascetic Authority in

Jerome’s Letters from the Syrian Desert,” 500.

[13] Jerome,

Letter (CXXVII) 127.1 and 127.4, respectively as quoted, in Nicene

and Post-Nicene Fathers.

[14]

Jerome, Letter 66.1 (LXVI), in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.

[15] Jerome,

Letter 108. (LXVI), in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.

[16] Jerome,

Letter 128.1 (LXXVIII), in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.

[17] Jerome’s

letter is found in the collection of Augustine’s Letters, number 202. The above

taken from a translation by J.G. Cunningham, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers,

First Series, Vol. 1., ed. by Philip Schaff (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature

Publishing Co., 1887.), revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin

Knight, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1102202.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment