The 14th of September marks the Feast of the

Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

A Bit of History

The Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross dates back to 335 A.D. at the dedication

of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre: the location believed to be where Jesus’

body was interred. The 14th September marked the second day of a

festival commemorating the relic of the true cross, brought out of the church

for the veneration of the faithful.

.jpg/479px-Helena_of_Constantinople_(Cima_da_Conegliano).jpg) |

| Saint Helena of Constantinople, National Gallery of Art (US). |

It is traditionally believed that the relic of the true

cross, upon which Jesus was crucified, was discovered nine years earlier in 326

(according to some accounts, even earlier) by St. Helena—the mother of the

Roman Emperor Constantine—whilst on pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

Theodoret’s (d. 457 A.D.) account goes as follows:

When the empress beheld the place

where the Saviour suffered, she immediately ordered the idolatrous temple [of

Venus], which had been there erected [probably under Hadrian], to be destroyed,

and the very earth on which it stood to be removed. When the tomb, which had

been so long concealed, was discovered, three crosses were seen buried near the

Lord's sepulchre. All held it as certain that one of these crosses was that of

our Lord Jesus Christ, and that the other two were those of the thieves who

were crucified with Him. Yet they could not discern to which of the three the

Body of the Lord had been brought nigh, and which had received the outpouring

of His precious Blood. But the wise and holy Macarius, the president of the

city, resolved this question in the following manner. He caused a lady of rank,

who had been long suffering from disease, to be touched by each of the crosses,

with earnest prayer, and thus discerned the virtue residing in that of the

Saviour. For the instant this cross was brought near the lady, it expelled the

sore disease, and made her whole.[1]

Purpose of the Feast

Outside of this specific historical context, the feast

day is a dedicated day on which the Church celebrates and recognises the

mystery of the Cross as the instrument of universal salvation, and as the

perennial symbol of God’s love for us. Interestingly, the word “salvation” in

Greek in its broadest sense refers to health, wellbeing and welfare in the

holistic sense, the body included. This ties in with Theodoret’s account above

which involves the healing of an ill woman by means of the cross.

Outside of this specific historical context, the feast

day is a dedicated day on which the Church celebrates and recognises the

mystery of the Cross as the instrument of universal salvation, and as the

perennial symbol of God’s love for us. Interestingly, the word “salvation” in

Greek in its broadest sense refers to health, wellbeing and welfare in the

holistic sense, the body included. This ties in with Theodoret’s account above

which involves the healing of an ill woman by means of the cross.

On the Cross, God’s love is made

manifest—demonstrated in the Crucified-One, wounded and bloody, nailed with

arms open in a gesture of the Word, that speaks louder than words. A gesture

which comprises the message of the Gospel, the Good News, that “God so

loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whoever believes in

him shall not perish but would have eternal life.” (Jn 3:16).

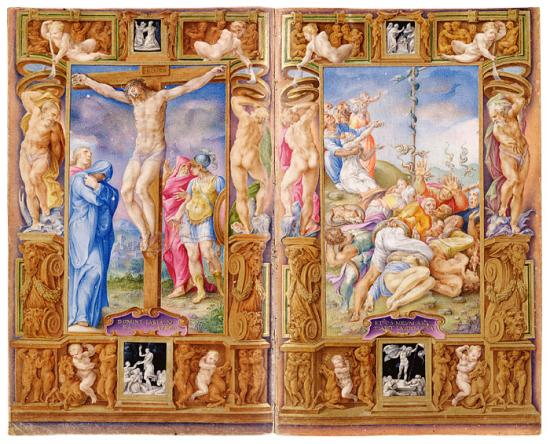

Moses and the Bronze Serpent

A key motif of the readings designated for the Mass of the Feast is the bronze serpent

which Moses lifted up in the wilderness. To cut a short story shorter: the

Israelites, who despite been delivered miraculously from the slavery of Egypt,

were complaining once again about God and the leadership of Moses. Serpents are

sent as a result, and many of the people are bitten and die. In turn the people

plead with Moses to intercede with God. Moses pleads, God answers and tells him

to fashion a serpent from bronze, and to place it on a stand and lift it up.

Moses is told that anyone who is bitten who looks at this serpent, will be

healed. Moses does as he is told, and the people are healed by gazing at the

bronze serpent.

Jesus—The Bronze Serpent

In the Gospel of John, Jesus draws a direct parallel with

his pending crucifixion and the bronze serpent of Moses:

And as Moses lifted up the serpent

in the desert, so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in

him, may not perish; but may have life everlasting. (Jn 3:15).

Here Jesus explains that the bronze serpent of Moses was

merely a foreshadowing of His being lifted up on the standard of the Cross. As

gazing upon the former bronze serpent brought about the physical and temporal

healing of the body, so the gazing in faith upon Jesus Crucified, as the only

Son of the Father sent to die for our sins, brings about the spiritual and

eternal healing of the soul by means of redemption.

The Biter Got Bit

The Old Testament recounts that the cause of the people’s

ailment was the bite from serpents. This reminds us of the Genesis creation

account, where a serpent (interpreted as Satan in disguise) deceives Eve and

leads her to sin by breaking God’s command and eating the forbidden fruit. Adam

joins the party, and we have what the Church calls Original Sin: the first sin,

which is the cause of our ‘natural’ state of disunion with God.

In a figurative sense, we can say that by achieving the

deception of Eve, Satan in the guise of a serpent bit Eve, ironically through

her biting into the forbidden fruit; and by Adam’s yielding to Eve’s invitation

to bite the fruit, Adam was bit in turn. The poison of concupiscence—of evil

inclination—was injected into their souls, and thus into every human being

henceforth. Fundamentally good, yes, but now inclined towards evil.

The poison: concupiscence. The ailment: Original Sin. The

remedy: the true bronze serpent—Jesus Christ, the Saviour of the world, who was

lifted up on the Cross, that whosoever looks upon Him with the eyes of their

heart, believing that He is the Son of God, Love Incarnate, will in turn be

healed interiorly.

Baptism: The First Look

Baptism is ordinarily the first look—a turning of the

eyes of the soul in faith, towards Jesus—which heals the soul of the ailment of

Original Sin. Adults do so by their own faith, young children by the faith of

their parents. Those baptised past the age of reason are healed of all personal

sin as well—those under age not having any to be healed of. Yet life happens,

we’re imperfect creatures, and so we need to return to the divine physician.

Confession: Extraction and Anti-Venom

Thus, the Sacrament of Reconciliation, of Confession comes

into play, which is one of the two key sacramental ways in which the soul gazes

upon Christ. The sacrament restores and renews the soul’s health by extracting the

poison of concupiscence in the form of personal sin.

Mortal sin is like a fatal

dose of such poison, from which the soul must be revived; and each venial sin a

non-fatal dose, smaller or larger, which needs to be extracted to restore the

soul to full health. The Sacrament of Confession sacramentally accomplishes

this.

Private and personal repenting

in perfect contrition is essential and also accomplishes this, yet it ought to

serve as a staple-compliment to the frequenting of Confession as minimally required

by the wisdom of the Church, and in the instance of mortal sin, must be followed

by a hasty Confession.

The Sacrament of Mercy, as

Pope Francis so calls it, is a load-lightening gift from God. It’s the hospital

bed every Catholic is invited to lie upon. Our embarrassment stemming from pride

ought not keep us away! It would be akin to one of the Israelites, if upon

being instructed that gazing upon the bronze serpent would heal him, refused to

do so, simply out of pride of not admitting he was bitten. Like the bronze

serpent, held up by Moses for all to see, Christ is there, hanging on the

Cross, spiritually waiting in our hearts for our repentance, and in the

confessional to absolve us. Healing itself, as a God-Man, reaches out to us,

all we need is to take hold of the opportunity while we have it.

Confession is not only the

means for extracting the poison of sins committed, but it administers the anti-venom

of God’s grace, bestowed through this Sacrament, which strengths the soul against

further “bites”.

We may not always feel it

emotionally, perhaps somewhere deeper down—but regardless, the reality takes

place: the bloodstream of the soul is cleansed by this Sacrament. Reviving the

soul with a joy and peace the world cannot give.

St. Pope John Paul II understood this well, and is why he supposedly frequented Confession every day! Not that everyone should frequent the sacrament every day, since this could fan scrupulosity in many, but nonetheless, as usual, the saints show us what’s important and inspire us to imitate in accord with our unique personality. We are asked to do so at least once a year, but weekly, fortnightly, or monthly, is an excellent practice.

St. Pope John Paul II understood this well, and is why he supposedly frequented Confession every day! Not that everyone should frequent the sacrament every day, since this could fan scrupulosity in many, but nonetheless, as usual, the saints show us what’s important and inspire us to imitate in accord with our unique personality. We are asked to do so at least once a year, but weekly, fortnightly, or monthly, is an excellent practice.

The Eucharist: The Healer in Our Midst

|

| "Jesus giving Communion to the Apostles," Joos Van Wassenhove, 1472. |

The Holy Eucharist is the crème de la crème of the Sacraments.

The remedy of remedies. The most important sacramental means by which we look

upon Christ. The Sacrament by which we not only gaze in Adoration upon the

Crucified Christ, disguised under the appearance of bread; but by which we come

into real contact with the Healer of our Souls in the reception of Holy

Communion.

CCC 1394 states: “As bodily

nourishment restores lost strength, so the Eucharist strengthens our charity,

which tends to be weakened in daily life; and this living charity wipes away

venial sins.” Indeed, reception of the Eucharist is our manna in the wilderness

of this life. It strengthens us in our pilgrimage to heaven, and in our mission

to love God and neighbour alike. By receiving His wounded and glorified Body,

we are healed and sanctified—instantly in soul, and by pledge, in our bodies. By

receiving His innocent and pure Blood, are own blood, poisoned with sin, is

transfused with His innocence and purity.

Funnily enough, the temporal manna was part of the reason

the Israelites were complaining against God and Moses. They were sick of it. Sadly,

as Catholics, we often lose sight of the glorious reality of the Eucharist, and

the supreme gift and fount of grace which it is.

Like the Israelites, we can

grow indifferent to the Eucharist, perhaps even losing faith in the Real

Presence—that Jesus isn’t simply symbolised by the bread and wine, but that He is

truly and really present under the outward form of bread and wine. This is why

it’s important to call out to Jesus, like the people called out to Moses,

asking Jesus to give us the faith we need to believe He is with us in the Eucharist.

And if we already have such faith, to call out to Jesus that He might spread

that belief so that all would come to taste the beauty of this Sacrament which restores the soul who beholds the Healer behind the mask.

The serpents came to the Israelites

as a result of their ingratitude and indifference to God’s gift in the temporal

manna. This teaches us that when we knowingly put Jesus in the Eucharist to

one-side, without letting the Eucharist be at the center of our lives, we unnecessarily

open ourselves to various kinds spiritual serpents which will attack our faith,

hope and love.

The Loving Gaze of Adoration

|

| 'Healing the Man Born Blind," Duccio, 1308 - 1311. |

St. Augustine commends us to adore Him who we receive.

Beyond reception of Jesus in the Eucharist, by which we consume the Divine

Healer and Physician into our souls, Eucharistic Adoration is the means by

which we lovingly gaze into Him who although is before us sacramentally, is

mysteriously within us by grace. These loving gazes which we cast upon Jesus in

the Eucharist vivify our souls in grace, and infuse in us blessings which will

endure in paradise.

Yet Jesus gazes out upon us as

well, peering through the lattice of the accidents of bread and wine (Song 2:9)—penetrating

our souls with a gaze which melts and heals the soul in love. So profound is

this invisible gaze of love, hardly able to be sustained at its climax, that in

respect to the soul and to Jesus, the words from the Song of Solomon apply:

“Turn away thine eyes from me, for they have overcome me” (6:5). Or as might

otherwise be translated: “they have overwhelmed me”, “they have captured me”.

The time we dedicate and set aside to spend in the presence

of Jesus in the Eucharist, is time spent under the standard of the true bronze

serpent, Christ Crucified—time not wasted, as the economic mind-set of the

world would see it, but time invested in healing us, and through us, the

Mystical Body of Christ. Since when we come before Jesus in the Blessed

Sacrament, we bring everyone along with us, past, present and future. When we

adore, we must therefore cultivate that sense of adoring on behalf of everyone.

For in our gazes on Jesus, we can gaze on behalf of all, in the faith that as

Jesus pours healing on us, He is pouring healing on the entire world in every

generation. Since Jesus’ love and healing cannot be confined by space or time.

The Glance of Prayer

Then comes prayer. Personal and private prayer, carried

out in the secrecy of our hearts. There is no limit to the amount of times we

can turn the eyes of soul in faith, towards the standard of the Cross.

Silently. Perhaps with a word of praise or invocation through the day. By means

of devotionals, such as the Rosary, wherein we join Mary in Her perfect and

profound gaze on Jesus.

Joining in the Perfect Gaze of Mary

Indeed, we cannot forget Mary. She alone can teach us the

art of that loving and trusting look. That uncompromising gaze which is fixed passionately

on Jesus, in profound reverence and confidence. It’s a good thing we can claim

in faith, Mary’s own perfect-loving gaze. In time, we will be swept up by it as

Joseph was, who through Mary perfected this art in his own right. Gazing upon

Jesus as an infant, and worshipping Him in his heart. In turn, John the Beloved

became an apprentice of this trade, studying under the Virgin Mary. The trade

of Adoration, passed down through the ages from loving soul, to loving soul.

The Moses-Call: Lift Up!

What else can be said but a summons to imitate Moses, who

lifted up the bronze serpent for the healing of the people. Sure, the

ministerial priest does this very act in a unique and remarkable way, at the

elevation of the Host, and in Eucharist processions and Benedictions. Yet as

baptised Christians, we are members of the royal priesthood—the priesthood

which the Church teaches is common to all. By means of this priesthood, we have

the privilege and the responsibility to lift up Jesus in our hearts, through

our worship and praise. In prayer, deed and in our very lives, by our witness

in ordinary living.

At its worst the countenance

of a Christian can be a moralistic harbinger of judgement, an illuministic

plaster void of authentic spirit, or a pietistic mask grinning as an expression

of a “love-bomb” technique that seeks to proselytise for reasons of self-glory instead

of sincere love. But at its best, the countenance of a Christian can radiate

the healing presence of Christ, through a genuinely human smile, a hearty

laugh, or a look of appreciation and recognition—especially to those “bitten”

by society and pushed into the shadows. The poor, the homeless, the elderly. Yet

the business man and the cash register deserve no less. Everyone unknowingly

suffers from the original “bite” and the poison of sin, and thus everyone

intrinsically craves for the healing which comes from meeting eye to eye with Christ.

The nearest they might get is a genuine look from someone like ourselves—and as

imperfect as we are, God’s love within us transcends it all.

The fashioning of the bronze serpent and the healing derived therefrom, arose from the intercessory prayer of Moses. Thus in addition to lifting Jesus up in our interior lives and

exterior lives, is lifting Jesus up in prayer carried out in the Spirit for the benefit of others. Prayer

which is simply filled with the intent to bring Jesus to all so that spiritual

healing might come to all the nations and their people—to every man, woman and

child. Do we not know that by a simple intent we can spiritually lift up the

Cross of Christ in any country, town or home, thereby bringing healing to such

places, to those open to such graces? We do not need to be physically present,

all we need is the faith and desire to do so. “Ask and you shall receive.” We

can raise up the standard of the Cross even into the realms of purgatory, thereby

placing before the holy souls the Crucified One, who upon gazing upon Him they’ll

be able to increase in healing, quickening their time of purgation, all by

means of such prayer.

We can visit the dying, even

if we cannot be physically present. We can visit the sick, and imprisoned.

Nothing substitutes for a physical presence, unless of course our state and

vocation in life dictates otherwise, but such ministry carried out spiritually can

accompany our concrete deeds, all by means of faith. By praying for anyone, we

attend to them in the Spirit, and join them in drinking from the healing poured

out upon those who gaze in trust upon the Lord.

Conclusion

Moses brought the bronze standard to the people, thereby

bringing them healing. Let us carry forth the Cross of Christ, in prayer, word

and deed, in our hearts and on our walls, to all people, especially those in

our parishes, schools, families, workplaces and communities. The Gospel, the Goods

News, that “God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that

whoever believes in him shall not perish but would have eternal life” is preached

the loudest by one who lifts up the cross in their own life, by embracing it

with full vigour, eyes fixed on Christ, and directed towards the peak of

Calvary to join Him in the consummation of love.

This gaze involves the

Sacraments, it involves Mary after the pattern of Joseph; prayer and adoration,

corporeal acts of mercy, and spiritual acts of mercy. All these solidify the

gaze of love which finds its fulfillment in beatitude.

On this note, the words of the

peasant who used to spend hours in front of Jesus in the Eucharist, apply—as a

call to adore, and as offering an insight into what heaven will essentially

involve. One day, the Cure de Ars asked the peasant, “What do you say to Jesus

during all this time of prayer?” The peasant simply responded, “Nothing, I look

at Him and He looks at me.”

[1]

Theodoret, Ecclesiastical History Chapter xvii. “Venus” inserted as per the

account of Eusebius on the Holy Sepulchre, and “Hadrian” as per being the most

likely historical candidate.